Day of the Dead Celebration

Celebrando el Día de Muertos

The Day of the Dead is one of the most important celebrations in Mexico. Since pre-Hispanic times, every November 1 and 2 Mexicans gather to honor their deceased.

Historical and anthropological studies have made it possible to verify that the celebrations dedicated to the dead not only share an ancient ceremonial practice in which the Catholic and pre-Columbian traditions coexist, but also manifestations that are based on the ethnic and cultural plurality of the country.

Despite how ancient the tradition may be, some curious facts are still unknown. For this reason, we took on the task of compiling some and that we will share with you below.

El Día de Muertos es una de las celebraciones más importantes en México. Desde la época prehispánica, cada 1 y 2 de noviembre los mexicanos se reúnen para honrar a sus difuntos.

Estudios históricos y antropológicos han permitido constatar que las celebraciones dedicadas a los muertos, no solo comparten una antigua práctica ceremonial en la que conviven la tradición católica y la precolombina, sino también manifestaciones que se sustentan en la pluralidad étnica y cultural del país.

A pesar de lo milenaria que pueda ser la tradición a continuación te compartimos algunos datos curiosos.

Origins of La Catrina

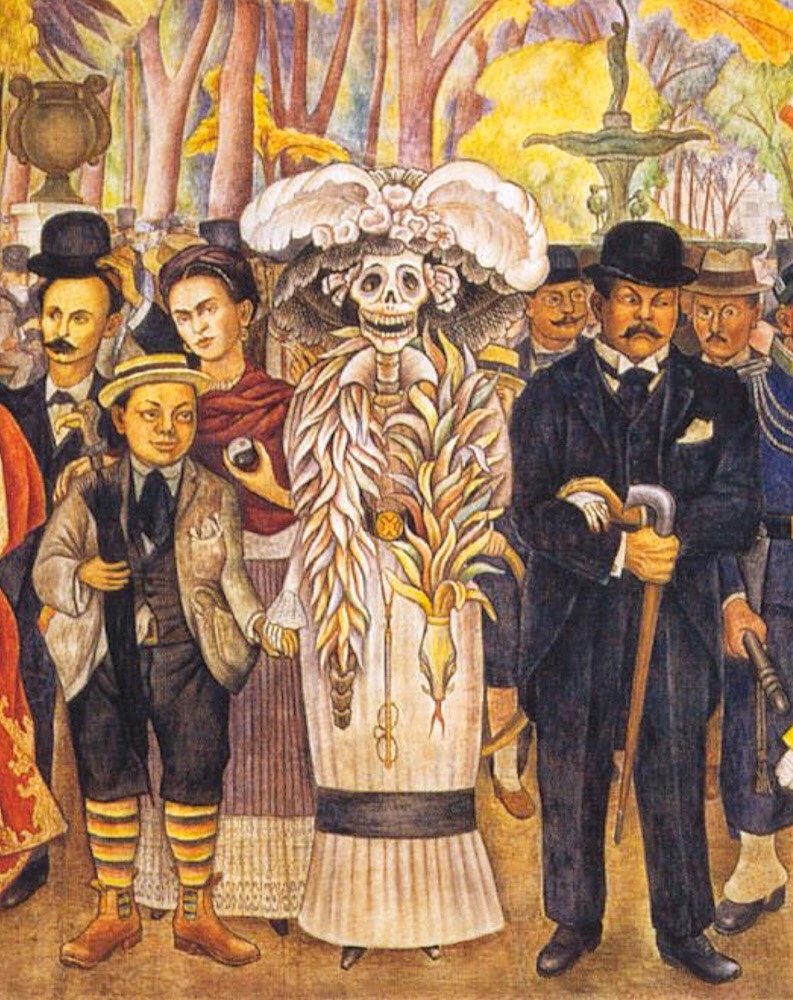

La Catrina, originally called La Calavera Garbancera, is a figure created by José Guadalupe Posada and baptized by the muralist Diego Rivera.

José Guadalupe Posada was the first to use this emblematic character, in his famous engraving “La Calavera Garbancera”, to criticize the so-called garbanceros, people of indigenous blood who pretended to be Europeans.

Years later, Diego Rivera created the image of La Catrina as we know it today.

With this peculiar character, the muralist also criticized the Mexican aristocracy. La Catrina’s first appearance was in the mural “Dream of a Sunday afternoon in the Alameda Central.”

The Catrina is the symbol of death and the icon of the day of the dead in Mexico. La Catrina is a skeleton woman who wears a large French-style hat over her skull1 and is the Mexican representation of death. … Its meaning is that death makes us all equal, rich and poor.

Orígenes de la Catrina

La Catrina, originalmente llamada La Calavera Garbancera, es una figura creada por José Guadalupe Posada y bautizada por el muralista Diego Rivera.José Guadalupe Posada fue el primero en utilizar este emblemático personaje, en su famoso grabado “La Calavera Garbancera”, para criticar a los llamados garbanceros, personas de sangre indígena que pretendían ser europeos.

Años después, Diego Rivera creó la imagen de La Catrina como la conocemos en la actualidad.

Con este peculiar personaje, el también muralista hacía una crítica a la aristocracia mexicana. La primera aparición de La Catrina fue en el mural “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central”.

La Catrina es el símbolo de la muerte y el ícono del día de muertos en México. La Catrina es una mujer esqueleto que lleva un gran sombrero de estilo francés sobre su calavera y es la representación mexicana de la muerte. … Su significado es que la muerte nos iguala a todos, ricos y pobres.

The offering for the faithful departed

According to the pre-Hispanic calendar, each deity sponsored a specific period of time. The offerings belonging to Mictlantecuchtli, lord of the dead, coincided with the month of November in the Gregorian calendar. The Spaniards, in their mission to institutionalize Christianity in Mesoamerican lands, decided to tie both visions, engendering a very complex syncretism that gave life to some festivals such as the Day of the Dead.

It is because of this cultural mix that today an offering cannot be imagined without a cross, a photo of the deceased and marigold flowers.

Tradition indicates that the altar begins to be assembled from October 30 or 31 and remains until November 2 or 3 depending on the region of Mexico

La ofrenda para los fieles difuntos

De acuerdo con el calendario prehispánico, cada deidad patrocinaba un espacio de tiempo determinado. Las ofrendas pertenecientes a Mictlantecuchtli, señor de los muertos, coincidían con el mes de noviembre en el calendario gregoriano. Los españoles, en su misión por institucionalizar el cristianismo en tierras mesoamericanas, decidieron empatar ambas visiones, engendrando un sincretismo muy complejo que dio vida a algunas fiestas como las del Día de Muertos.

Es por esta mezcla cultural que hoy no se puede imaginar una ofrenda sin una cruz, la foto del difunto y flores de cempasúchil.

La tradición señala que el altar comienza a montarse desde el 30 o 31 de octubre y permanece hasta el 2 o 3 de noviembre dependiendo la región de México

Cempasúchil, the flower of the dead

Known above all for being one of the most popular ornaments on Day of the Dead tombs and offerings, the “twenty-petal flower” (for its roots in the Nahuatl language cempoal-xochitl, twenty-flower) only blooms after the time of rains.

Of an intense yellow color, the stem of the marigold can measure up to one meter in height, while its buttons can reach five centimeters in diameter. For this reason, the Mexica, during pre-Hispanic times, chose it to fill the altars, offerings and burials dedicated to their dead with hundreds of specimens.

Cempasúchil, la flor de los muertos

Conocida sobre todo por ser uno de los adornos más populares en las tumbas y ofrendas de Día de Muertos, la “flor de veinte pétalos” (por sus raíces en lengua náhuatl cempoal-xochitl, veinte-flor) sólo florece después de la época de lluvias.

De color amarillo intenso, el tallo de la cempasúchil puede llegar a medir hasta un metro de altura, mientras que sus botones pueden alcanzar los cinco centímetros de diámetro. Por ello los mexicas, durante la época prehispánica, la eligieron para tupir con cientos de ejemplares los altares, ofrendas y entierros dedicados a sus muertos.

Day of the dead is not Halloween

Day of the Dead is not the “Mexican Halloween” like it is sometimes mistaken to be because of the timing of the year. The two holidays originated with similar afterlife beliefs but are very different in modern day. Halloween began as a Celtic Festival where people would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off ghosts but has recently turned into a tradition of costume wearing and trick-or-treating. Decorating your house with spiders and bats and wearing scary costumes is not done in most parts of Mexico.

El día de los muertos no es Halloween

El Día de los Muertos no es el “Halloween mexicano” como a veces se confunde debido a la época del año. Los dos días festivos se originaron con creencias similares en el más allá, pero son muy diferentes en la actualidad. Halloween comenzó como un festival celta en el que la gente encendía hogueras y usaba disfraces para protegerse de los fantasmas, pero recientemente se ha convertido en una tradición de disfraces y truco o trato. Decorar tu casa con arañas y murciélagos y usar disfraces aterradores no se hace en la mayor parte de México.

World Heritage

In 2003, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) declared this holiday as a “Masterpiece of the cultural heritage of humanity” as it represents one of the most relevant examples of the living heritage of Mexico and the world.

Patrimonio de la humanidad

En el año 2003, la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (Unesco) declaró esta festividad como “Obra maestra del patrimonio cultural de la humanidad” ya que representa uno de los ejemplos más relevantes del patrimonio vivo de México y del mundo.

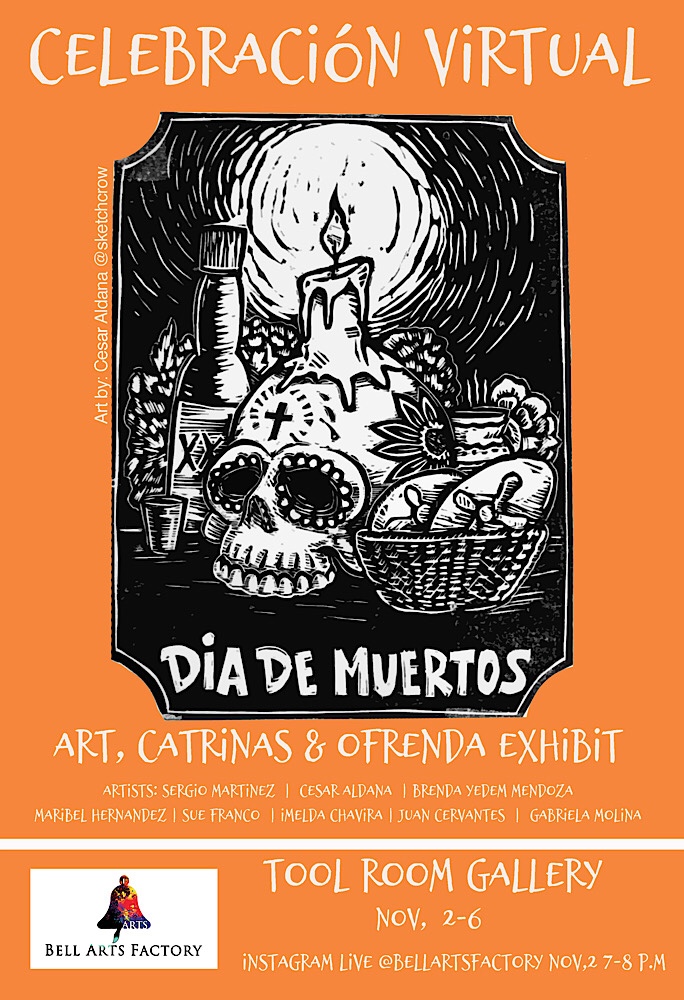

Please mark your calendars

&

join our

Virtual Celebration

via Instagram LIVE

from the Tool Room Gallery.

Exhibit will include:

Art, a Catrina Procession

and of course our Ofrenda

Nov 2nd, 2020

7:00 pm to 8:00 pm

Artists included in our

Tool Room Gallery Exhibit

are:

Sergio Martínez

Cesar Aldana

Maribel Hernández

Sué Franco

Imelda Chavira

Juan Cervantes

Gabriela Molina

See you in our Instagram LIVE!

Exhibit will be open for personal viewing

by appointment only

Nov 2nd – Nov 6th

contact: info@bellartsfactory.org

Support Bell Arts Factory